What happens when the tools we use to observe the universe start colliding, both literally and figuratively, with the tools we’re sending into it? A groundbreaking study has revealed that Starlink satellites are leaking unintended radio signals into astronomy-critical bands, threatening the work of next-generation observatories like SKA-Low. The emissions, detected in nearly 30% of images over a 29-day period, aren’t just a minor inconvenience, they could also derail efforts to study the early universe. Meanwhile, the Vera Rubin Observatory, poised to launch one of the most ambitious sky surveys in history, is bracing for another kind of interference: satellite streaks across its wide-field images, caused by the ever-growing swarm of broadband constellations.

Though only a fraction of each Rubin image is affected, the sheer volume of streaks and the complexity of correcting them pose a serious engineering and operational headache. Astronomers are fighting back with smarter scheduling, better software, and even some image processing tricks, but it’s an uphill battle from here. What’s most concerning is how both issues, radio leakage and optical pollution, are symptoms of the same problem: a lack of foresight in regulating mega-constellations. With tens of thousands more satellites on the way, the margin for error is disappearing. If we want to preserve our ability to study the cosmos, we need satellite operators, regulators, and scientists to get on the same page. The skies may be getting more connected, but they’re also getting a lot less quiet.

Let’s dive in.

In This Issue

Starlink satellites are leaking radio signals that may ruin astronomy

Satellite streaks: Can the huge new Vera Rubin Observatory function in the megaconstellation age?

Companies may soon pay a fee for their rockets to share the skies with airplanes

Would a Planetary Sunshade Help Cool the Planet? This Mission Could Find Out

The Orbital Servicing Wars - Part I: A Brief History till Date

Secure World Foundation Letter of Support 2025 ORBITS Act

Starlink satellites are leaking radio signals that may ruin astronomy

A major new study led by Dylan Grigg, Steven Tingay, and Marcin Sokolowski reveals that Starlink satellites are flooding key radio astronomy frequencies with unintended emissions, and it’s worse than anyone thought. Using the SKA-Low prototype station in Western Australia, the team analyzed 76 million sky images over 29 days and identified emissions from over 1,800 unique Starlink satellites. Alarming levels of unintended electromagnetic radiation (UEMR) were detected not just across science-critical frequencies but also in internationally protected bands. In some datasets, nearly 30% of all sky images captured included at least one Starlink signal!

The researchers found that newer Starlink models, especially the v2-mini Ku-band and Direct-to-Cell versions, dominate the interference landscape. These satellites emitted both narrowband and broadband signals, often outside their designated transmission frequencies. Even more concerning, these emissions were found at power levels far exceeding safe thresholds for delicate radio astronomy experiments like those attempting to detect the faint signals from the Epoch of Reionisation. If this trend continues unchecked, it could cripple SKA-Low’s ability to achieve its science goals.

While some of the emissions are likely the result of spacecraft systems like propulsion or avionics, others appear to be reflections of Earth-based FM signals, meaning even terrestrial noise is bouncing off satellites and back down to Earth in quiet zones. Despite existing International Telecommunication Union protections, current regulations don’t account for this kind of unintended leakage. That regulatory blind spot is becoming a glaring problem as mega-constellations multiply in orbit.

The team is calling for stronger oversight, more transparency from satellite operators, and urgent updates to international rules. Their full dataset (openly available) is meant to serve as a benchmark for policymakers and scientists alike.

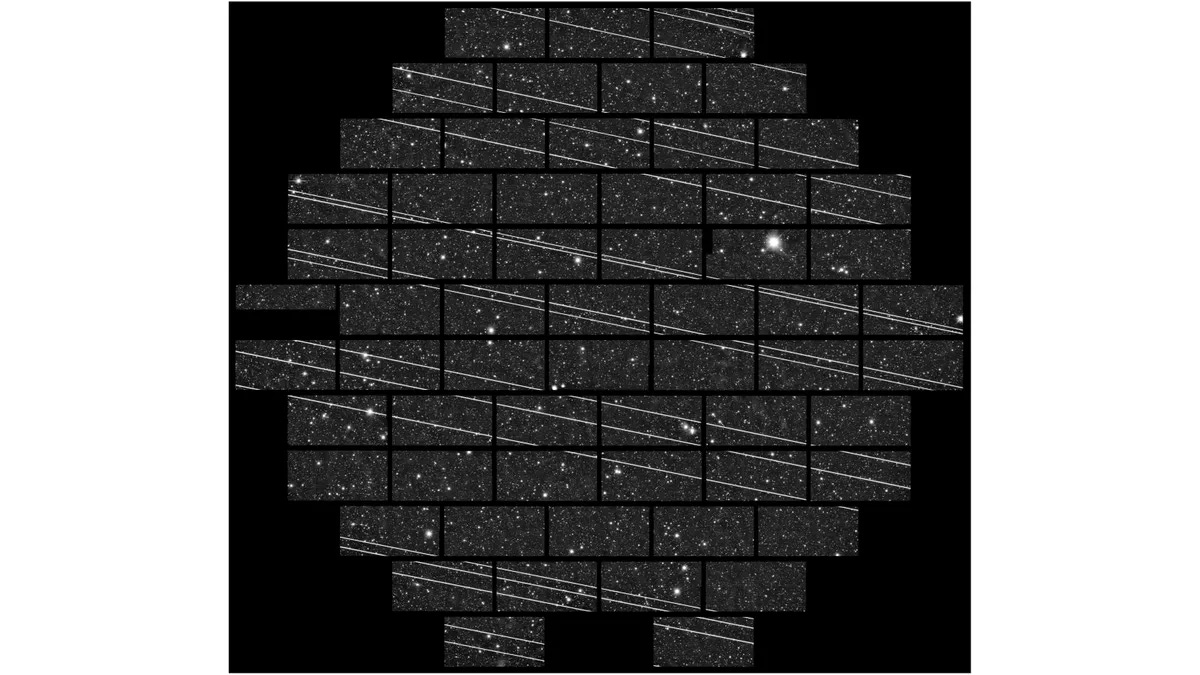

Satellite streaks: Can the huge new Vera Rubin Observatory function in the megaconstellation age?

As the Vera C. Rubin Observatory gears up for its long-awaited sky survey, it’s facing a modern space-age dilemma: satellite streaks slicing through its ultra-wide images. Thanks to mega-constellations like Starlink, bright trails from satellites now regularly photobomb astronomical observations. While these streaks affect only a tiny portion of each image (roughly 0.04% of pixels, even in worst-case scenarios) they pose new challenges for researchers trying to extract clean, uninterrupted data from the cosmos.

Thankfully, astronomers aren’t starting from scratch. The observatory’s team is building sophisticated software tools to detect and mask these streaks, while also exploring smarter scheduling and slewing strategies to minimize disruption. Even with tens of thousands of satellites in orbit, researchers believe the observatory’s science mission can still be achieved, though it’ll take careful planning and digital cleanup. It’s an engineering headache, not a showstopper.

This growing interference connects directly to another major concern: Starlink satellites are also leaking unintended radio signals, as flagged in the study using the SKA-Low prototype. Between optical streaks and radio noise, the once quiet night sky is getting louder and messier. Together, these developments are forcing a reckoning: if mega-constellations are here to stay, observatories and satellite operators must find ways to coexist, or risk undermining our ability to study the universe.

Companies may soon pay a fee for their rockets to share the skies with airplanes

The skies above Earth are getting crowded, and now, space companies may soon have to start paying for the traffic jam. A new proposal from the FAA, backed by Sen. Ted Cruz, suggests launching a fee system where rocket operators pay based on how much payload they’re sending up. Starting in 2026, companies could be charged $0.25 per pound (capped at $30,000 per launch), ramping up to $1.50 per pound by 2033. The goal would be to help fund the FAA’s Commercial Space Office, which is juggling an ever-growing number of rocket launches and airspace closures that affect aviation traffic below.

It’s a small slice of a launch budget, especially for big players like SpaceX, but it’s sparking some debate in the industry. Critics argue the fee structure could unfairly hit heavy-lift rockets or smaller launch startups trying to stay afloat. Some are pushing for a flat fee per launch instead. But with satellite mega-constellations and daily launches on the horizon, something’s gotta give, and the FAA needs the resources to keep air and space traffic moving safely and efficiently.

If this plan lifts off, it could be a game-changer for space regulation. More launches mean more airspace coordination, and more pressure on the FAA to keep things orderly. By directly funding the office responsible for launch approvals and airspace integration, the proposal could finally give regulators the runway they need to match the pace of NewSpace. As the commercial space sector expands, this charge-per-pound approach may emerge as a pragmatic solution to balance innovation with regulatory readiness.

Would a Planetary Sunshade Help Cool the Planet? This Mission Could Find Out

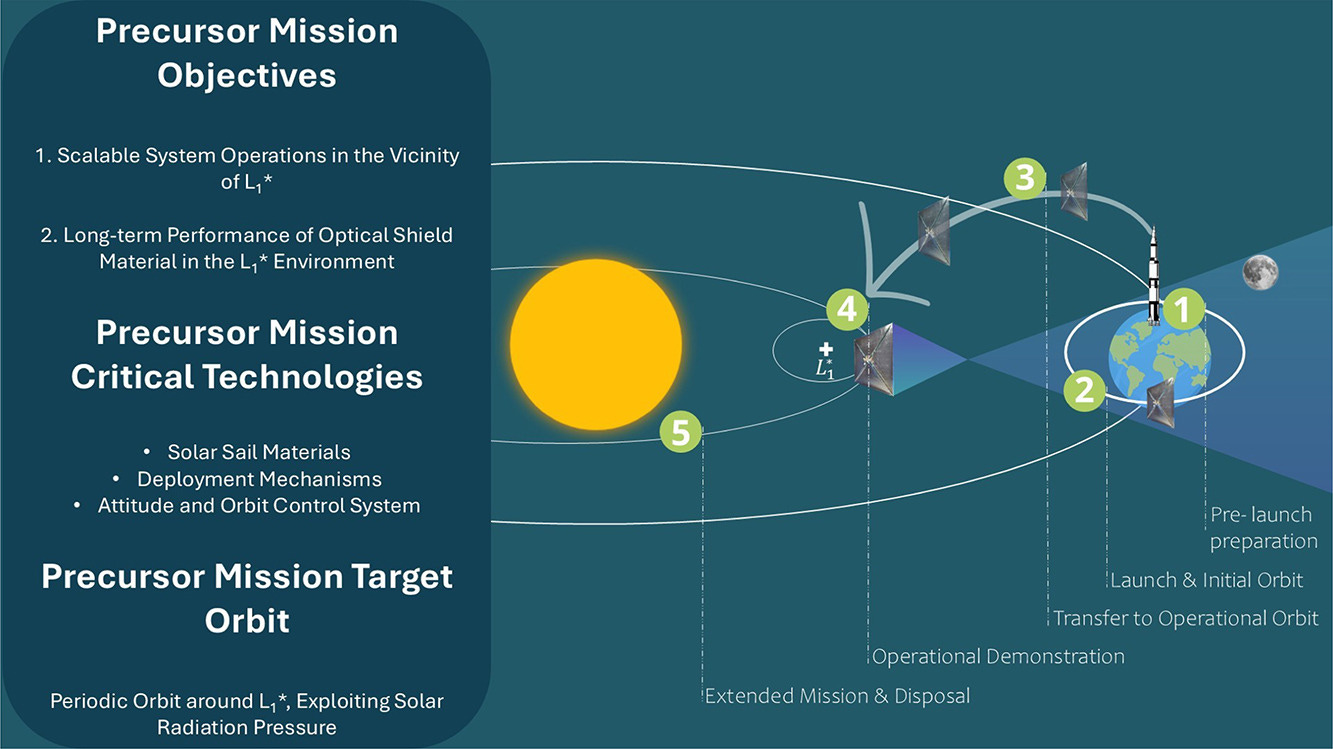

Scientists are exploring an audacious strategy to cool our warming planet: deploying a planetary sunshade at the Earth-Sun L1 Lagrange point. Led by Marina Coco at the Polytechnic University of Turin, the proposed system would consist of a massive reflective shield held in place by the subtle pressure of sunlight. This would be akin to a giant cosmic umbrella designed to cast a steady, temperature-lowering shadow over our planet.

To test this bold concept, researchers plan to launch a 12U CubeSat equipped with a massive 144 m² solar sail, weighing just 15–20 kg. This demo mission aims to validate two critical technologies: advanced optical materials that can survive prolonged exposure to radiation and debris, and solar sailing propulsion, which uses sunlight itself to maintain precise positioning without traditional fuel .

While a full-scale sunshade (spanning potentially millions of square kilometers) remains decades away and would require massive launch capabilities, this early mission could unlock proof-of-concept data essential for future climate-engineering efforts. With greenhouse gas emissions still climbing, the sunshade isn’t a carbon fix, but a high-stakes geoengineering tool that might help us buy some time while global emissions are tamed

The Orbital Servicing Wars - Part I: A Brief History till Date

In his latest article, Adithya Kothandhapani sets the stage for one of the most important space races you’ve probably never heard of: the battle to control orbital servicing. As satellite constellations grow and orbital real estate gets more crowded, simply deorbiting or replacing broken spacecraft won’t cut it. The future lies in fixing, refueling, and upgrading satellites in space, and the players lining up to lead this charge are taking wildly different approaches.

Kothandhapani paints a vivid picture of three competing strategies. The U.S. is betting on scrappy startups and commercial innovation to lead the way, Europe is opting for cautious coordination and standards, while China is steadily evolving from state-led missions to a hybrid government-commercial model. Each region’s playbook reflects its broader space philosophy: speed and disruption vs. structure and control. As a result, we are witnessing a high-stakes chess match in orbit, with long-term dominance on the line.

But this isn’t just about robotic arms and docking maneuvers, it’s also about rewriting the rules of orbital ownership, consent, and cooperation. Who decides who can service what? What happens when missions go wrong? And how do we build trust in a domain where one misstep could trigger diplomatic fallout, or even orbital chaos? The orbital servicing game is heating up fast, and the winners will shape the economics of space, and even define its future.

Secure World Foundation Letter of Support 2025 ORBITS Act

The Secure World Foundation (SWF) is throwing its full support behind the 2025 ORBITS Act, a bipartisan bill that could finally put the U.S. at the forefront of space debris cleanup. The ORBITS Act proposes a demonstration program for active debris removal (ADR) and the creation of uniform orbital debris standards. In other words, it’s the kind of long-overdue federal push the U.S. space sector needs to tackle the growing crisis of orbital junk head-on.

The SWF emphasizes that while debris mitigation helps slow the problem, it does nothing to clean up what’s already up there, and it’s the legacy debris from past U.S., Soviet, and Chinese missions that now poses the greatest threat. Other nations like Japan, the UK, and EU members are already funding ADR pilot projects through private companies. The U.S., meanwhile, risks falling behind. By investing in real technology and codifying standards, the ORBITS Act could set a global example and secure the long-term safety, sustainability, and competitiveness of American space assets.

Interesting Posts & Videos

The Zero Debris movement is gaining serious momentum. At the 2025 Zero Debris Future Symposium, ESA celebrated a major milestone: launched in 2023, the Zero Debris Charter now boasts 177 signatories! This year’s discussions dove into the commercial and policy realities of cleaning up space, with a strong focus on how sustainability and competitiveness can go hand-in-hand.

Eric Dahlstrom is seeking lunar infrastructure experts to support a student project at ISU SSP25 in Seoul (June 30–Aug 22). The focus: building sustainable lunar bases that reduce Earth dependence and protect the Moon’s environment. Experts in areas like ISRU, life support, power, policy, or lunar construction are invited to answer occasional questions mid-July to early August. Interested in shaping the future of lunar exploration? Sign up - Project brief.

BSI Aerospace has released BSI Flex 1971 v1.0 for public consultation, a new sustainability standard aimed at reducing the environmental impact of orbital and suborbital launches. The guidance should help organizations manage risks, improve sustainability, and align with global best practices across the entire launch lifecycle. Backed by the UK Space Agency, the draft is open for feedback until 27 July.

Conferences & Webinars

Space Debris Training Course 2025: call for applications now open - Apply by June 23, 2025 - ESEC-Galaxia, Belgium

The 7th Summit for Space Sustainability - October 22-23, 2025

Centre de Conférences Pierre Mendès France, Paris

Thanks for reading.

Until next time!